Lovely Conservatism

Brief thoughts in Favour of Conservatism in matters of Reform

|

| A drawing of Edmund Burke, the great conservative British statesman and philosopher. |

I am currently reading C. S. Lewis' Abolition of Man, a small 1943 book that criticises modern philosophy 'in defence of traditional values'. It is an excellent book that I find to be very thought-provoking, especially for us modern people who, in my estimation, have gone too far with our subjectivist and relativist philosophies. Lewis challenges our modern sensibilities by presenting an alternative worldview, which is not only traditional (that is to say, universal across time) but also cross-cultural (that is to say, universal across space).

During my reading of the book, there were these few paragraphs that really struck me. It is what inspired me to write this post, and it strikes me as a remarkably insightful and edifying sentiment. In the second chapter of the book, titled The Way, he addresses a common objection to Traditionalism, which states that the worldview is incapable of any reform or progress. In response to this, he writes:

"Does this mean, then, that no progress in our perceptions of value can ever take place? That we are bound down for ever to an unchanging code given once for all? And is it, in any event, possible to talk of obeying what I call the Tao [the term he uses to refer to Traditional Values]? If we lump together, as I have done, the traditional moralities of East and West, the Christian the Pagan, and the Jew, shall we not find many contradictions and some absurdities? I admit all this. Some criticism, some removal of contradictions, even some real development, is required. But there are two very different kinds of criticism.

A theorist about language may approach his native tongue, as it were from outside, regarding its genius as a thing that has no claim on him and advocating wholesale alterations of its idiom and spelling in the interests of commercial convenience or scientific accuracy. That is one thing. A great poet, who has 'loved, and been well nurtured in his mother tongue', may also make great alterations in it, but his changes of the language are made in the spirit of the language itself; he works from within. The language which suffers, has also inspired, the changes. That is a different thing - as different as the works of Shakespeare are from basic English. It is the difference between alteration from within and alteration from without: between the organic and the surgical.

In the same way, the Tao admits development from within. There is a difference between a real moral advance and a mere innovation. From the Confucian 'Do not do to others what you would not like them to do to you' to the Christian 'Do as you would be done by' is a real advance. The morality of Nietzsche is a mere innovation. The first is an advance because no one who did not admit the validity of the old maxim could see reason for accepting the new one, and anyone who accepted the old would at once recognize the new as an extension of the same principle. If he rejected it, he would have to reject it as a superfluity, something that went too far, not as something simply heterogeneous from his own ideas of value. But the Nietzschean ethic can be accepted only if we are ready to scrap traditional morals as a mere error and then to put ourselves in a position where we can find no ground for any value judgments at all. It is the difference between a man who says to us: 'You like your vegetables moderately fresh; why not grow your own and have them perfectly fresh?' and a man who says, 'Throw away that loaf and try eating bricks and centipedes instead.'" (Lewis, pg 44-46)

The basic intuition of this passage is summarised by the last sentence of the second paragraph, that the difference between proper reform and ruinous reform depends on the difference between alteration from within and alteration from without: between the organic and the surgical. To my mind, these distinct attitudes towards reform represent the views of the political left and right. The Left seems to analyse societies from external vantage points, resulting in radical and revolutionary social prescriptions, many of which often break with social traditions. In contrast to this, the Right is more cautious and conservative, for it seeks to accomplish change organically, reforming society in accordance with its own traditions and values.

|

| The French Revolution exemplifies the Left's tendency towards revolutionary change. It was characterised by a radical desire to completely overturn the social order for greater equality and justice for the poorer classes. Unfortunately, the Revolution resulted in mass bloodshed and violence. |

I think the conservative approach is more noble than the progressive approach. Whereas the 'surgical' is artificial, doing violence to the natural way of things, the 'organic' is authentic, being in accord with the true nature of things. I doubt that my preference for the 'natural' over and against the 'unnatural' will be at all popular among more progressively-minded readers. Indeed, they may even say that such a dichotomy is not real but a mere fiction constructed by oppressive institutions and powers throughout history. But this position is ultimately untenable, especially for the Left, for it undercuts some of their most dearly-held beliefs and values.

Recall that these Leftists are often the greatest defenders of individual authenticity and expression, for they criticise restrictive social forces in the name of personal freedoms. If they are to attack the common-sense intuition that there really exists that which is 'natural' and that which is 'unnatural', then they must let go of their commitment to individual authenticity, for that is just naturality by another name (as what is authentic to individuals is that which comes naturally to them). But this would be catastrophic to every single Leftist project. How could socialists decry neoliberal capitalism without appealing to a 'natural' healthy standard of human work and production? How would feminists criticise patriarchy without appealing to the 'natural' individuality of every woman? How could LGBT activists criticise heteronormativity without appealing to the naturality of non-conforming identities? How could revolutionary artists challenge norms and conventions without appealing to the authenticity of their work and lived experiences? These programs could not achieve their desired social ends without relying upon the conservative assumption. This teaching is inescapable, and one can only reject at one's own peril.

Now, I must admit that I am not unbiased in my assessment of this principle. The conservative assumption is defended with extreme ferocity within my native religious tradition of Islam. Human Naturality, by which I mean all those things that are 'natural' and 'normal' to human beings, is seen as the key ingredient to happiness and welfare. This principle is crystalized in the doctrine of Fitra (فطرة), the primordial, original and natural state of humanity that Islam seeks to recover in every human being. Social Innovations that subvert and challenge traditional norms are understood in the concept of Bid'ah (بدعة), which, though permitted at times, is mostly treated with great suspicion and concern. I suspect Islam is not the only religion that keeps this kind of attitude in matters of social change and reform.

The conservative assumption has important implications when applied to various social issues and phenomena. I will consider one application of it here, and that will be on the issue of Patriotism. Whereas the Left is often skeptical of nationalistic sentiments, regarding them as sentimental and irrational notions, the political Right is very defensive of these traditional values. The conservative assumption helps explain why this is the case. Patriotism enables one to identify with one's nation and identify it as belonging to one's identity. The patriot sees her nation as a good for herself and seeks to partake of that good by participating in its traditions, customs, and social affairs. Whenever her nation needs political reform, the patriot approaches this problem through the conservative mindset of 'organic' reform from the inside, so to speak, in opposition to 'surgical' reform from the outside. Just as the poet has "been well-nurtured by his mother tongue", so too has the patriot been well-nurtured by her motherland. It is her love for her native soil that inspires and motivates her to pursue reform, carrying the spirit of the nation itself.

This patriotic attitude stands in stark contrast to the cosmopolitan liberalism of the modernized and Westernized world, which sees national identities as mere aesthetic relics of a bygone age. I don't know why this contrast exists, as it is a relatively new phenomenon in human history. Now, there are considerations of history and geography that are relevant here. Many Europeans, whose civilizations have barbarously ravaged and pillaged colonised lands, understandably feel shameful about their national identities, for they have done so much injustice to other nations. However, the same nationalist spirit the imperialists used to degrade their colonies was itself used against the colonists by many independence movements throughout the world. In my native Indonesia, Nationalism is a key part of the political landscape because it was the driving engine of Independence from the Dutch and other foreign powers.

|

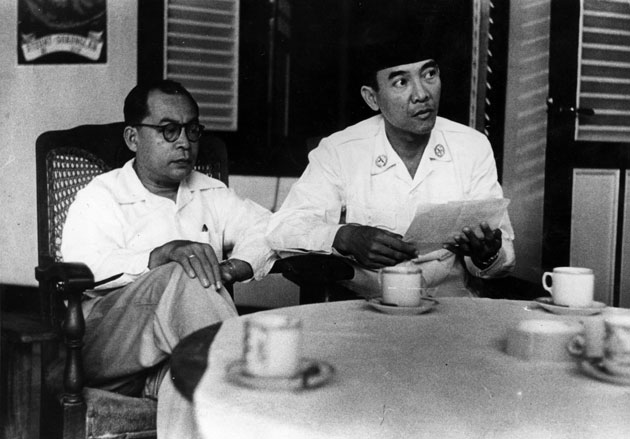

| This is an image of Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta, major leaders in the Indonesian Independence Struggle and the first President and Vice President of the young Nation, respectively. Indonesia's great nation-builders were all staunch nationalists, and this spirit was immensely influential in the formation of Indonesia's orthodox political theory called Pancasila. |

I cannot shake the feeling that the anti-nationalist sentiments of liberals and progressives are mere Western prejudices propagated to the rest of the world. In my eyes, it's always the more privileged and 'modernised' members of the nation that tend to be antinationalists. I suspect that if I were to ask a Javanese villager about their nationalism, they would answer with resounding enthusiasm. However, were I to pose that same question to one who is more westernised, they would act as if they had just been charged with a great crime and adamantly deny that charge. I fail to see much appeal in this unpatriotic attitude.

Now, leftists may criticise nationalism on the grounds that it is a dangerous ideology because it can often be coopted by malevolent powers and authorities, turning it into a big stumbling block against social progress and reform. I believe this point to be very valid and do not disagree with it whatsoever. But, I believe the opposite can also be true, that patriotic nationalism is an indispensable tool for political reform and change. Something that immediately comes to my mind is the social and political contradistinction within the Civil Rights Movement in the United States between Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s pacifist integrationism and Malcolm X's Black separatism. Though both are undoubtedly great men of incredible intellect and will, my limited understanding of History tells me that King had an overall larger impact on the American public vis a vis Malcolm X. I suspect that the difference in their two approaches had something to do with this. Malcolm X, though he was a Traditionalist through and through, promoted political change of a 'surgical' character, attacking the American nation as inherently evil and corrupt. This seems to be the approach of modern 'antiracist' activists in the US political landscape. On the other hand, King appealed to America's self-professed values and ideals to push for 'organic' reform and change. In this respect, he more closely resembled that great orator and reformer, Frederick Douglass. I'm certain there are many more examples of 'organic' patriotism being a stronger means to social change than 'surgical' criticism, but I am not nearly knowledgeable enough on this matter to comment more.

There are likely many other social issues that this analysis can be applied to, but those will be topics for other posts and authors. Here, I simply wanted to comment on this conservative assumption, which seems universal and is also integral to so many different ideologies and worldviews. I will likely return to this principle in future posts, but what I have written here will suffice for this one.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment